The Picture of Dorian Gray

| The Picture of Dorian Gray | |

|---|---|

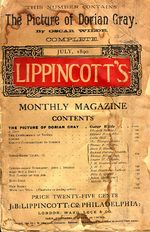

Cover of the first edition |

|

| Author | Oscar Wilde |

| Language | English |

| Genre(s) | Gothic fiction |

| Publisher | Lippincott's Monthly Magazine |

| Publication date | 1890 |

| Media type | |

| ISBN | ISBN 0-14-143957-2 (Modern paperback edition) |

| OCLC Number | 53071567 |

| Dewey Decimal | 823/.8 22 |

| LC Classification | PR5819.A2 M543 2003 |

The Picture of Dorian Gray is the only published novel by Oscar Wilde, appearing as the lead story in Lippincott's Monthly Magazine on 20 June 1890, printed as the July 1890 issue of this magazine.[1] Wilde later revised this edition, making several alterations, and adding new chapters; the amended version was published by Ward, Lock, and Company in April 1891.[2] The title is often translated The Portrait of Dorian Gray.

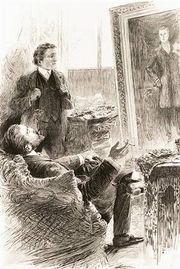

The novel tells of a young man named Dorian Gray, the subject of a painting by artist Basil Hallward. Basil is impressed by Dorian's beauty and becomes infatuated with him, believing his beauty is responsible for a new mode in his art. Dorian meets Lord Henry Wotton, a friend of Basil's, and becomes enthralled by Lord Henry's world view. Espousing a new hedonism, Lord Henry suggests the only things worth pursuing in life are beauty and fulfillment of the senses. Realizing that one day his beauty will fade, Dorian (whimsically) expresses a desire to sell his soul to ensure the portrait, Basil has painted, would age rather than himself. Dorian's wish is fulfilled, plunging him into debauched acts. The portrait serves as a reminder of the effect each act has upon his soul, with each sin displayed as a disfigurement of his form, or through a sign of aging.[3]

The Picture of Dorian Gray is considered a work of classic gothic horror fiction with a strong Faustian theme.[4]

Contents |

Plot summary

The novel begins with Lord Henry Wotton observing the artist Basil Hallward painting the portrait of a handsome young man named Dorian Gray. Dorian arrives later and meets Wotton. After hearing Lord Henry's world view, Dorian begins to think beauty is the only worthwhile aspect of life, the only thing left to pursue. He wishes that the portrait Basil is painting would grow old in his place. Under the influence of Lord Henry (who relishes the hedonic lifestyle and is a major exponent thereof), Dorian begins to explore his senses. He discovers actress Sibyl Vane, who performs Shakespeare in a dingy theatre. Dorian approaches her and soon proposes marriage. Sibyl, who refers to him as "Prince Charming," rushes home to tell her skeptical mother and brother. Her protective brother James tells her that if "Prince Charming" harms her, he will certainly kill him.

Dorian invites Basil and Lord Henry to see Sibyl perform in Romeo and Juliet. Sibyl, whose only knowledge of love was love of theatre, loses her acting abilities through the experience of true love with Dorian. Dorian rejects her, saying her beauty was in her art, and he is no longer interested in her if she can no longer act. When he returns home he notices that his portrait has changed. Dorian realizes his wish has come true – the portrait now bears a subtle sneer and will age with each sin he commits, whilst his own appearance remains unchanged. He decides to reconcile with Sibyl, but Lord Henry arrives in the morning to say Sibyl has killed herself by swallowing prussic acid (hydrogen cyanide). With the persuasion and encouragement of Lord Henry, Dorian realizes that lust and looks are where his life is headed and he needs nothing else. That marks the end of Dorian's last and only true love affair. Over the next 18 years, Dorian experiments with every vice, mostly under the influence of a "poisonous" French novel, a present from Lord Henry. Wilde never reveals the title, but his inspiration was possibly drawn from Joris-Karl Huysmans's À rebours (Against Nature) due to the likenesses that exist between the two novels.[5]

One night, before he leaves for Paris, Basil arrives to question Dorian about rumours of his indulgences. Dorian does not deny his debauchery. He takes Basil to the portrait, which is as hideous as Dorian's sins. In anger, Dorian blames the artist for his fate and stabs Basil to death. He then blackmails an old friend named Alan Campbell, who is a chemist, into destroying Basil's body. Wishing to escape his crime, Dorian travels to an opium den. James Vane is nearby and hears someone refer to Dorian as "Prince Charming." He follows Dorian outside and attempts to shoot him, but he is deceived when Dorian asks James to look at him in the light, saying he is too young to have been involved with Sibyl 18 years earlier. James releases Dorian but is approached by a woman from the opium den who chastises him for not killing Dorian and tells him Dorian has not aged for 18 years.

While at dinner, Dorian sees James stalking the grounds and fears for his life. However, during a game-shooting party a few days later, a lurking James is accidentally shot and killed by one of the hunters. After returning to London, Dorian informs Lord Henry that he will be good from now on, and has started by not breaking the heart of his latest innocent conquest, a vicar's daughter in a country town, named Hetty Merton. At his apartment, Dorian wonders if the portrait has begun to change back, losing its senile, sinful appearance now that he has given up his immoral ways. He unveils the portrait to find it has become worse. Seeing this, he questions the motives behind his "mercy," whether it was merely vanity, curiosity, or the quest for new emotional excess. Deciding that only full confession will absolve him, but lacking feelings of guilt and fearing the consequences, he decides to destroy the last vestige of his conscience. In a rage, he picks up the knife that killed Basil Hallward and plunges it into the painting. His servants hear a cry from inside the locked room and send for the police. They find Dorian's body, stabbed in the heart and suddenly aged, withered and horrible. It is only through the rings on his hand that the corpse can be identified. Beside him, however, the portrait has reverted to its original form.

Characters

In a letter, Wilde said the main characters were reflections of himself: "Basil Hallward is what I think I am: Lord Henry is what the world thinks me: Dorian is what I would like to be—in other ages, perhaps".[6]

The main characters are:

- Dorian Gray – a handsome young man who becomes enthralled with Lord Henry's idea of a new hedonism. He begins to indulge in every kind of pleasure, moral and immoral.

- Basil Hallward – an artist who becomes infatuated with Dorian's beauty. Dorian helps Basil to realize his artistic potential, as Basil's portrait of Dorian proves to be his finest work.

- Lord Henry "Harry" Wotton – a nobleman who is a friend to Basil initially, but later becomes more intrigued with Dorian's beauty and naïvety. Extremely witty, Lord Henry is seen as a critique of Victorian culture at the end of the century, espousing a view of indulgent hedonism. He conveys to Dorian his world view, and Dorian becomes corrupted as he attempts to emulate him.

Other characters include:

- Sibyl Vane – An exceptionally talented and beautiful (though extremely poor) actress with whom Dorian falls in love. Her love for Dorian destroys her acting ability, as she no longer finds pleasure in portraying fictional love when she is experiencing love in reality. She commits suicide when she realizes Dorian no longer loves her.

- James Vane – Sibyl's brother who is to become a sailor and leave for Australia. He is extremely protective of his sister, especially as his mother is useless and concerned only with Dorian's money. He is hesitant to leave his sister, believing Dorian will harm her and promises to be vengeful if any harm should come to her. He is later killed in a hunting accident.

- Alan Campbell – a chemist and once a good friend of Dorian; he ended their friendship when Dorian's reputation began to come into question.

- Lord Fermor – Lord Henry's uncle. He informs Lord Henry about Dorian's lineage.

- Victoria, Lady Henry Wotton – Lord Henry's wife, who only appears once in the novel while Dorian waits for Lord Henry; she later divorces Lord Henry in exchange for a pianist.

Themes

Aestheticism and duplicity

Aestheticism is a strong motif and is tied in with the concept of the double life. A major theme is that aestheticism is merely an absurd abstract that only serves to disillusion rather than dignify the concept of beauty. Although Dorian is hedonistic, when Basil accuses him of making Lord Henry's sister's name a "by-word," Dorian replies "Take care, Basil. You go too far"[7] suggesting Dorian still cares about his outward image and standing within Victorian society. Wilde highlights Dorian's pleasure of living a double life.[8] Not only does Dorian enjoy this sensation in private, but he also feels "keenly the terrible pleasure of a double life" when attending a society gathering just 24 hours after committing a murder.

This duplicity and indulgence is most evident in Dorian's visit to the opium dens of London. Wilde conflates the images of the upper class and lower class by having the supposedly upright Dorian visit the impoverished districts of London. Lord Henry asserts that "crime belongs exclusively to the lower orders... I should fancy that crime was to them what art is to us, simply a method of procuring extraordinary sensations", which suggests that Dorian is both the criminal and the aesthete combined in one man. This is perhaps linked to Robert Louis Stevenson's Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, which Wilde admired.[1] The division that was witnessed in Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, although extreme, is evident in Dorian Gray, who attempts to contain the two divergent parts of his personality. This is a recurring theme in many Gothic novels.

Influence and responsibility

Influence is a recurring theme throughout the book. Influence is largely depicted by the author as immoral, as it eventually may turn people toward decisions that are not true to themselves, as best exemplified by Dorian Gray. However, all people are influenced and act as influences, and ironically, the book itself may influence its reader, though the preface paradoxically states that no artist, in their work, "desires to prove anything" or has "ethical sympathies." Dorian Gray is influenced toward his life of decadence by the hedonist philosophy of Lord Henry; prior to this, Dorian was perceived as innocent and inexperienced. Dorian's painting also influenced him, though it was merely a work of art. Basil, too, was influenced by his own painting of Dorian.

In addition to influence is the problem of who is to be held responsible for certain actions. Dorian's major flaw is that he is never able to hold himself accountable, instead, avoiding admission of responsibility by justifying his actions according to the philosophy of the new hedonism. When Sibyll commits suicide, Dorian distances himself from the blame by viewing her death as a work of art—a sort of tragic drama. In his frenzy to assign the responsibility to anyone but himself, Dorian blames Basil for the path his life has taken. In killing Basil, the narrator even writes the scene to demonstrate Dorian's perception that it is the knife that commits the murder, leaving Dorian himself, again, blameless. At the end of the novel, when it occurs to Dorian that he might confess, he instead chooses to destroy the painting, which he sees as the only piece of evidence that remains of his moral crimes.

Allusions to other works

The Republic

Glaucon and Adeimantus present the myth of Gyges' ring, by which Gyges made himself invisible. They ask Socrates, if one came into possession of such a ring, why should he act justly? Socrates replies that even if no one can see one's physical appearance, the soul is disfigured by the evils one commits. This disfigured (the antithesis of beautiful) and corrupt soul is imbalanced and disordered, and in itself undesirable regardless of other advantages of acting unjustly. Dorian Gray's portrait is the means by which other individuals, such as Dorian's friend Basil, may see Dorian's distorted soul.

Tannhäuser

At one point, Dorian Gray attends a performance of Richard Wagner's opera, Tannhäuser, and is explicitly said to personally identify with the work. Indeed, the opera bears some striking resemblances with the novel, and, in short, tells the story of a medieval (and historically real) singer, whose art is so beautiful that he causes Venus, the goddess of love herself, to fall in love with him, and to offer him eternal life with her in the Venusberg. Tannhäuser becomes dissatisfied with his life there, however, and elects to return to the harsh world of reality, where, after taking part in a song-contest, he is sternly censured for his sensuality, and eventually dies in his search for repentance and the love of a good woman.

Faust

Wilde is reputed to have stated that "in every first novel the hero is the author as Christ or Faust."[9] As in Faust, a temptation is placed before the lead character Dorian, the potential for ageless beauty; Dorian indulges in this temptation. In both stories, the lead character entices a beautiful woman to love them and kills not only her, but also that woman's brother, who seeks revenge.[10] Wilde went on to say that the notion behind The Picture of Dorian Gray is "old in the history of literature" but was something to which he had "given a new form."[11]

Unlike Faust, there is no point at which Dorian makes a deal with the devil. However, Lord Henry's cynical outlook on life, and hedonistic nature seems to be in keeping with the idea of the devil's role, that of the temptation of the pure and innocent, qualities which Dorian exemplifies at the beginning of the book. Although Lord Henry takes an interest in Dorian, it does not seem that he is aware of the effect of his actions. However, Lord Henry advises Dorian that "the only way to get rid of a temptation is to yield to it. Resist it, and your soul grows sick with longing";[12] in this sense, Lord Henry can be seen to represent the Devil, "leading Dorian into an unholy pact by manipulating his innocence and insecurity."[13]

Shakespeare

In his preface, Wilde writes about Caliban, a character from Shakespeare's play The Tempest. When Dorian is telling Lord Henry Wotton about his new 'love', Sibyl Vane, he refers to all of the Shakespearean plays she has been in, referring to her as the heroine of each play. At a later time, he speaks of his life by quoting Hamlet, who has similarly driven his girlfriend to suicide and her brother to swear revenge.

Joris-Karl Huysmans

Dorian Gray's "poisonous French novel" that leads to his downfall is believed to be Joris-Karl Huysmans' novel À rebours. Literary critic Richard Ellmann writes:

Wilde does not name the book but at his trial he conceded that it was, or almost, Huysmans's A Rebours...To a correspondent he wrote that he had played a 'fantastic variation' upon A Rebours and some day must write it down. The references in Dorian Gray to specific chapters are deliberately inaccurate.[14]

Literary significance

The Picture of Dorian Gray began as a short novel submitted to Lippincott's Monthly Magazine. In 1889, J. M. Stoddart, a proprietor for Lippincott, was in London to solicit short novels for the magazine. Wilde submitted the first version of The Picture of Dorian Gray, which was published on 20 June 1890 in the July edition of Lippincott's. There was a delay in getting Wilde's work to press while numerous changes were made to the novel (several manuscripts of which survive). Some of these changes were made at Wilde's instigation, and some at Stoddart's. Wilde removed all references to the fictitious book "Le Secret de Raoul", and to its fictitious author, Catulle Sarrazin. The book and its author are still referred to in the published versions of the novel, but are unnamed.

Wilde also attempted to moderate some of the more homoerotic instances in the book, or instances whereby the intentions of the characters may be misconstrued. In the 1890 edition, Basil tells Henry how he "worships" Dorian, and begs him not to "take away the one person that makes my life absolutely lovely to me." The focus for Basil in the 1890 edition seems to be more towards love, whereas the Basil of the 1891 edition cares more for his art, saying "the one person who gives my art whatever charm it may possess: my life as an artist depends on him." The book was also extended greatly: the original thirteen chapters became twenty, and the final chapter was divided into two new chapters. The additions involved the "fleshing out of Dorian as a character" and also provided details about his ancestry, which helped to make his "psychological collapse more prolonged and more convincing."[15] The character of James Vane was also introduced, which helped to elaborate upon Sibyl Vane's character and background; the addition of the character helped to emphasise and foreshadow Dorian's selfish ways, as James sees through Dorian's character, and guesses upon his future dishonourable actions (the inclusion of James Vane's sub-plot also gives the novel a more typically Victorian tinge, part of Wilde's attempts to decrease the controversy surrounding the book). Another notable change is that in the latter half of the novel events were specified as taking place around Dorian Gray's 32nd birthday, on 7 November. After the changes, they were specified as taking place around Dorian Gray's 38th birthday, on 9 November, thereby extending the period of time over which the story occurs. The former date is also significant in that it coincides with the year in Wilde's life during which he was introduced to homosexual practices.

Preface

The preface to The Picture of Dorian Gray was added, along with other amendments, after the edition published in Lippincott's was criticised. Wilde used it to address the criticism and defend the novel's reputation.[16] It consists of a collection of statements about the role of the artist, art itself, and the value of beauty, and serves as an indicator of the way in which Wilde intends the novel to be read, as well as traces of Wilde's exposure to Daoism and the writings of the Chinese Daoist philosopher Chuang Tsu. Shortly before writing the preface, Wilde reviewed Herbert A. Giles's translation of the writings of Chuang Tsu.[17] In it he writes:

| “ | The honest ratepayer and his healthy family have no doubt often mocked at the dome-like forehead of the philosopher, and laughed over the strange perspective of the landscape that lies beneath him. If they really knew who he was, they would tremble. For Chuang Tsǔ spent his life in preaching the great creed of Inaction, and in pointing out the uselessness of all things.[18] | ” |

Criticism

Overall, initial critical reception of the book was poor, with the book gaining "certain notoriety for being 'mawkish and nauseous,' 'unclean,' 'effeminate,' and 'contaminating.'"[19] This had much to do with the novel's homoerotic overtones, which caused something of a sensation amongst Victorian critics when first published. A large portion of the criticism was levelled at Wilde's perceived hedonism, and its distorted views of conventional morality. The Daily Chronicle of 30 June 1890 suggests that Wilde's novel contains "one element...which will taint every young mind that comes in contact with it." The Scots Observer of 5 July 1890 asks why Wilde must "go grubbing in muck-heaps?” Wilde responded to such criticisms by curtailing some of the homoerotic overtones, and by adding six chapters to the book in an effort to add background.[20]

Major changes in the 1891 version from the 1890 first edition

The 1891 version was expanded from 13 to 20 chapters, but also toned down, particularly in some of its overt homoerotic aspects. Also, chapters 3, 5, and 15 to 18 are entirely new in the 1891 version, and chapter 13 from the first edition is split in two (becoming chapters 19 and 20).[21] At his 1895 trials Wilde testified that some of these changes were because of letters sent to him by Walter Pater.[22]

Deleted or moved passages

- (Basil about Dorian) He has stood as Paris in dainty armor, and as Adonis with huntsman's cloak and polished boar-spear. Crowned with heavy lotus-blossoms, he has sat on the prow of Adrian's barge, looking into the green, turbid Nile. He has leaned over the still pool of some Greek woodland, and seen in the water's silent silver the wonder of his own beauty. (This passage turns up in Basil's speech to Dorian in the 1891 version.)

- (Lord Henry about fidelity) It has nothing to do with our own will. It is either an unfortunate accident, or an unpleasant result of temperament.

- "You don't mean to say that Basil has got any passion or any romance in him?" / "I don't know whether he has any passion, but he certainly has romance," said Lord Henry, with an amused look in his eyes. / "Has he never let you know that?" / "Never. I must ask him about it. I am rather surprised to hear it.

- (Describing Basil Hallward) Rugged and straightforward as he was, there was something in his nature that was purely feminine in its tenderness.

- (Basil to Dorian) It is quite true that I have worshipped you with far more romance of feeling than a man usually gives to a friend. Somehow, I had never loved a woman. I suppose I never had time. Perhaps, as Harry says, a really grande passion is the privilege of those who have nothing to do, and that is the use of the idle classes in a country. (the latter remark being part of Lord Henry's dialogue in the 1891 version)

- Some dialogue between Mrs Leaf and Dorian has been cut, which mentions Dorian's fondness for "jam" (which might have been used metaphorically for his sexuality).

- When Basil confronts Dorian: Dorian, Dorian, your reputation is infamous. I know you and Harry are great friends. I say nothing about that now, but surely you need not have made his sister's name a by-word. (That part has been deleted in the 1891 version, and the passage after that has been added.)

Added passages

- Each class would have preached the importance of those virtues, for whose exercise there was no necessity in their own lives. The rich would have spoken on the value of thrift, and the idle grown eloquent over the dignity of labour.

- A grande passion is the privilege of people who have nothing to do. That is the one use of the idle classes of a country. Don't be afraid.

- Faithfulness! I must analyze it some day. The passion for property is in it. There are many things that we would throw away if we were not afraid that others might pick them up.

Adaptations and allusions

The Picture of Dorian Gray has been the subject of a great number of adaptations on television, film, and the stage. In addition to full adaptations, it has also been the subject of a number of other allusions.

- Adaptations

- Choreograper Matthew Bourne produced a contemporary dance adaptation of Dorian Gray.

- The film The Picture of Dorian Gray was released in 1945 and featured Hurd Hatfield as Dorian.

- Dorian, an Imitation is a 2002 novel by Will Self. The book is a modern take on Oscar Wilde's novel. Set in the 1980s and 90s, it follows Wilde's original closely, even retaining characters names with some alterations.

- The film Dorian Gray was released in 2009 and starred Ben Barnes as Dorian and Colin Firth as Lord Henry Wotton. The film was directed by Oliver Parker, who made some alterations to the plot (most notably moving the latter part of the plot to the early twentieth century).

- Allusions

- Dorian Gray was featured as a villainous character in the 2003 film The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen. In the original comic he never appears, but his distorted portrait appears in MI5 headquarters. Seemingly reluctant to join the League in the beginning, he violently reveals himself as a treasonous henchman for the film's antagonist. In the end, Gray is destroyed by another seemingly immortal League member, Mina Harker, who reveals his portrait to him, which breaks the spell. Gray screams as he ages hundreds of years in a matter of moments, crumbling to a skeleton as his likeness in the painting is restored.

- The Television Personalities produced a song titled "A Picture of Dorian Gray" as part of their debut album "And Don't the Kids Just Love It", recorded in 1980. The song has also been covered by the British post-punk revival band The Futureheads

- Referenced in the song "Sing for the Day" by the 1980s progressive rock band Styx, the lead singer is speaking to a girl named Hannah, and compares her with the line "...as ageless and timeless as Dorian Grey..."

- The character of Dorian Gray is referenced by Mötley Crüe in the song "New Tattoo" on the album of the same name.

- Dorian Gray is mentioned in the song "Narcissist" by The Libertines.

- The song "Dorian" by power metal band Demons & Wizards is based on the book.

- A line in the chorus part of the song "Tears and Rain" of the album Back to Bedlam by singer/songwriter James Blunt runs "All pleasure's the same: it just keeps me from trouble. Hides my true shape, like Dorian Gray."

- In the song "The Future Holds A Lion's Heart" by Darren Hayes, from the album, This Delicate Thing We've Made; there is a direct reference to the picture of Dorian Gray being placed in the attic. "When my heart was in the attic/ Like the picture of Dorian Gray"

- The 1994–2001 DC Comics series Starman featured a storyline based on Dorian Gray, in which the origins of the Oscar Wilde story are discussed, and Wilde is portrayed in flashbacks.

- Gary Larson has made reference to the novel in The Far Side, including the captions "The Picture of Dorian Cow" and "The Picture of Dorian Gray and his dog."

- In the Family Guy episode, "When You Wish Upon A Weinstein", Meg Griffin asks Stewie Griffin how she looks and he replies, "In an attic somewhere, there's a portrait of you getting prettier."

- A long time joke about the youthful appearance of Dick Clark was that he doesn't appear to age while a painted velvet portrait of Elvis in his attic ages instead.

- Punk trio Girl in a Coma references the novel in their song "Sybil Vane was Ill" from their debut cd "Both Before I'm Gone".

- The 2008 video game Fable 2 includes the character of Reaver, a bisexual mayor who has sold his soul to the Shadow Court for eternal youth. The character is first met having his portrait painted in a direct allusion to Dorian Gray. The character was voiced by Stephen Fry, who happened to play the title role in the 1997 film Wilde.

- In the U2 song "Crumbs From Your Table" a line of lyrics states, "You were pretty as a picture/ it was all there to see/ then your face caught up with your psychology." The song "The Ocean" from U2's debut album Boy has a line that goes, "Picture in grey, Dorian Gray,just me, by the sea".

- Chapter 353 of the manga Ghost Sweeper Mikami entitled "Dorian Grey's Painting" featured a plot that revolved around the paint used by Basil Hallward instead of the painting itself.

- The song "Dorian Gray" on the William Control CD, Noir (William Control album), alludes to the novel's story in its lyrics. The song implies that Dorian's life was one of utter loneliness, and he plans to willingly end it. Ultimately, it is implied he will go to hell.

- Plot borrowings

- The British show Blake's 7 featured a plot loosely based on the novel in the episode "Rescue".

- Star Trek: The Next Generation used the novel as inspiration for its 129th episode "Man of the People", featuring a Dorian Gray-esque diplomat who exorcises his own negative feelings by transferring them into others, placing crewmember Deanna Troi life in danger.

- Get Smart episode "Age Before Duty," features a plot to murder agents by applying "Dorian Gray Paint" on their photographs.

- In the AD&D Ravenloft supplement "Islands of Dread" a character named Stezen D'Polarno is featured whose personal curse is partly based on the story of Dorian Gray.

- The Warhammer 40k novel Fulgrim featured a plot loosely based on the novel.

- James Joyce employs references to Wilde's novel in the Proteus episode of Ulysses.

- Jasper Fforde's novel The Fourth Bear features an appearance by a character named Dorian Gray who sells a car to the protagonist, Jack Spratt. The car has a painting of itself in the trunk, which becomes damaged instead of the car.

- The television series "The Lair," which revolves around a coven of gay vampires, featured a character whose youth and power was linked to a portrait of himself, which changes as he ages. The character is frequently seen painting over the changed parts.

Modern attention

The Picture of Dorian Gray was chosen as the book of 2010 for Dublin City's "One City, One Book" Festival in its fifth year.[23] Cultural events related to the book and Oscar Wilde were hosted in Dublin during April 2010.

Editions

- The Picture of Dorian Gray, Wordsworth Classics 1992, ISBN 1853260150

- The Picture of Dorian Gray, Modern Library 1992, ISBN 978-0-679-60001-5

- The Picture of Dorian Gray, Penguin Classics 1988, ISBN 978-0140433187-X

- The Picture of Dorian Gray, Tor 1999, ISBN 0-812-56711-0

- The Picture of Dorian Gray, Books, Inc. 1994

- The Picture of Dorian Gray, Barnes and Noble Classics 2003, ISBN 978-1-59308-025-9

- The Picture of Dorian Gray, Macmillan Readers 2005, ISBN 978-0-230-02922-4

- The Picture or Dorian Gray, Macmillan Readers 2005 (with CD pack), ISBN 978-1-4050-7658-6

- The Picture of Dorian Gray, Penguin Classics 2006, ISBN 978-0141442037

- The Picture of Dorian Gray, Oxford World's Classics 2006, ISBN 978-0192807298

- The Picture of Dorian Gray, Oneworld Classics 2008, ISBN 978-1-84749-018-6

Footnotes and references

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 The Picture of Dorian Gray (Penguin Classics) – Introduction

- ↑ Notes on The Picture of Dorian Gray – An overview of the text, sources, influences, themes and a summary of The Picture of Dorian Gray

- ↑ The Picture of Dorian Gray (Project Gutenberg 20-chapter version), line 3479 et seq in plain text (chapter VII).

- ↑ Ghost and Horror Fiction – a website which discusses ghost and horror fiction from the 19th century onwards (retrieved 30 July 2006)

- ↑ "Wilde's The Picture of Dorian Gray". Highbeam Research. http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1G1-92865915.html. Retrieved 26 April 2007.

- ↑ The Modern Library – a synopsis of the book coupled with a short biography of Oscar Wilde (retrieved 3 November 2009)

- ↑ The Picture of Dorian Gray (Penguin Classics) – Chapter XII

- ↑ The Picture of Dorian Gray (Penguin Classics) – Chapter XI

- ↑ The Wikiquote Oscar Wilde page classifies this quotation as Unsourced.

- ↑ Oscar Wilde Quotes – a quote from Oscar Wilde about The Picture of Dorian Gray and its likeness to Faust (retrieved 7 July 2006)

- ↑ The Picture of Dorian Gray (Penguin Classics) – Preface

- ↑ The Picture of Dorian Gray (Penguin Classics) – Chapter II

- ↑ The Picture of Dorian Gray – a summary and commentary of Chapter II of The Picture of Dorian Gray (retrieved 29 July 2006)

- ↑ Ellmann, Oscar Wilde (Vintage, 1988) p.316

- ↑ The Picture of Dorian Gray (Penguin Classics) – A Note on the Text

- ↑ GraderSave: ClassicNote – a summary and analysis of the book and its preface (retrieved 5 July 2006)

- ↑ The Preface first appeared with the publication of the novel in 1891. But by June of 1890 Wilde was defending his book (see The Letters of Oscar Wilde, Merlin Holland and Rupert Hart-Davis eds., Henry Holt (2000), ISBN 0-8050-5915-6 and The Artist as Critic, ed. Richard Ellmann, University of Chicago (1968), ISBN 0-226-89764-8 – where Wilde's review of Giles's translation is reprinted and Chuang Tsŭ is incorrectly identified with Confucius.) Wilde's review of Giles's translation was published in The Speaker of 8 February 1890.

- ↑ Ellmann, The Artist as Critic, 222.

- ↑ The Modern Library – a synopsis of the book coupled with a short biography of Oscar Wilde (retrieved 6 July 2006)

- ↑ CliffsNotes:The Picture of Dorian Gray – an introduction and overview the book (retrieved 5 July 2006)

- ↑ "?". http://home.arcor.de/mdoege/dorian_gray_diff.html.

- ↑ Lawler, Donald L., "An Inquiry into Oscar Wilde's Revisions of 'The Picture of Dorian Gray'" (New York: Garland, 1988)

- ↑ Official website of Dublin: One City, One Book...an initiative of Dublin City Public Libraries. "?". http://www.dublinonecityonebook.ie/.

See also

- Adaptations of The Picture of Dorian Gray

- Dorian Gray syndrome

- List of cultural references in The Picture of Dorian Gray

- The Happy Hypocrite (in some ways an inverse of The Picture of Dorian Gray)

External links

- Replica of the 1890 Edition at University of Victoria

- The Picture of Dorian Gray to read on line on bibliomania site.

- The Picture of Dorian Gray (13-chapter version) at Project Gutenberg

- The Picture of Dorian Gray (20-chapter version) at Project Gutenberg

- Audioversion at Librivox

- The Picture of Dorian Gray study guide, themes, quotes, literary devices, character analyses, teacher resources